My body had just reached that state one notch above sleep last night; I was relaxed and warm under the comforter and my husband's arm, when my mind slapped me awake.

Christ, they have completely abandoned everything we've been taught in business school.

I bolted upright, startling my equally drowsy spouse, and began to scrabble for a pen and paper. I didn't want to blow this off as a dream. I scrawled a note in scant light, reminding myself that this was a nightmare and not a dream.

Everything I've been taught they've thrown out the door. They, being this presidential administration. Everything, being the basics we are taught in our earliest days of business school.

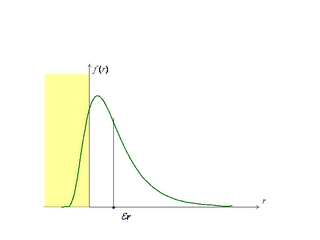

My mind must have continued to churn after last evening's Book Salon at FireDogLake; Crooked Timber's Henry Farrell and author Jacob Hacker dropped in to chat about Hacker's book, The Great Risk Shift. I've not yet read it, it's on my list (I'm afraid that I'm still backlogged on reading, too many piled up on the nightstand). Their book has elevated in priority in my reading queue now after last night's discussion. The premise of the book is that a sea change has occurred, affecting many aspects of our lives; in the process of acquiring and integrating right-wing ideology, businesses have transferred substantive amounts of risk to the consumer, to the population at large, instead of carrying it themselves either directly as expenses or indirectly as taxes that fund public services. The average American is exposed to so much more volatility, worrying about health care coverage and job security, while businesses look only at the numbers and ratchet down their risk by dialing up the exposure to their workers and their stakeholders.

How is this different from what we learned in business school? We're taught how to mitigate financial exposure by manipulating cash positions into higher yields or invest in capital improvements if the rate of financial return is higher than investments in stocks or bonds. We're taught to spread assets to minimize exposure, and how to insure business operations, as well as how to look for cost reductions.

But the first thing most business students learn is that entrepreneurs are risk takers, who are rewarded with profits for taking risk.

Day One lesson in General Business 101. Maybe Day Two. I'm certain if I go and dig out my class notes I will be able to confirm this.

And not one school, but three schools, and a Entrepreneurship Program taught me this. My junior college, my first college wherein I suffered through an unhappy start in engineering, and my final college, all of them said the same thing in their curriculums. Risk taking was MINE as a business owner, and for that I would be entitled to profits.

What the hell happened that it became so commonplace to push risk off on everybody else, to take the profits and run like wind?

Yet another point made early in my career as a business student was the nature of the free market economy. A free market was better and more efficient than all other economic forms, we were instructed in Econ I, Econ II, International Econ, and I'm sure in several other business classes; we were also told that a free market was most efficient when information was perfect. Perfect, meaning information was widely available to all players, and deep enough for businesses to be able to make highly informed decisions. While certain information is proprietary and confidential, most information should be as broadly accessible in a free market economy; even consumers needed this information to make informed purchasing decisions while communicating to vendors what products were successful or not.

But that's patently untrue today; information is bottlenecked and stifled. Were this not the case, Enron would never have succeeded in duping the public, nor would businesses see the remedies stipulated in Sarbanes-Oxley regulations as cumbersome. We'd also see all risks disclosed, including the loss of health care to production workers, as line items in our risk exposure analysis both internally and externally. And our government wouldn't be hiding M3 and real unemployment figures.

What the hell happened? How did these fundamental points become detritus to be discarded? Is there some new set of rules to which I'm supposed to manage my small business?

Why didn't I get the memo?

And how the hell am I going to sleep tonight?

Comments

I look at this whole free market thing from another point of view. Optimization algorithms are a deeply studied area of Computer Science. No Computer Scientist would argue that there is one and only one algorithm (the free market) that is suitable to all situations and data sets. Instead there are a plethora of algorithms and evaluation systems and their utility is dependent on the nature of the problem, the kind of answer that is sought, the size of the data set and a host of other factors. An awareness of the complexity inherent in the task underlies all my thinking about economics and society. I always wanted to see someone like Donald Knuth or Niklaus Wirth take Milton Friedman and wad him into a small ball and slam dunk him into the trash can. Alas, now that can never happen.

I recently spent 14 months with a startup. I came away with the conclusion that few venture capitalists are truly capable of assessing the risk of the investments they make. The system protects them from risk and is constructed to save them from themselves. Nothing protects you from risk like having lots of money. It's the poor guy who is fifty bucks short at the end of the month that suffers in our society.

Stuart

Are you enjoying your new house? We have finally begun construction on ours. We are in the midst of the construction of the foundation and have something tangible to look at. Next week our Structural Insulated Panels will show up.

Economics is not all about free markets, it is about utility maximization (achieving the maximum happiness for the lowest cost). You are right in the fact that information is key, but information is not without cost. Thus, those who buy or have access to the best information are typically better able to make choices -- given similar circumstances. This asymetry creates the opportunity for arbitrage.

Your comment "What the hell happened that it became so commonplace to push risk off on everybody else...?" This is a very important question.

I think it presupposes that we have been building something in our society with a particular purpose, some type of utopian steady-state estate. In a dynamic world, it is hard to maintain the "status quo." So risks shift, like sand. And if no one is maintaining and reorgainizing the shifting sands, someone else comes in and lays claims a patent, property right, or squatter's right to something they claim is new or abandoned. So they are granted title to the extent they can protect and defend their claim.

As far as I am able, I protect my house from decay, my professional liceneses and education from erosion, and my family from splintering. It is hard, and I have to replenish my energies with sleep, relaxation, exersize, food, and so on. Yet, there are only 24 hours in a day. So I can only fight the good fight for a few hours a day.

Corporations, on the otherhand, can be seen as synthetic individuals. From a sinister perspective, they can work 24 hours a day, seven days a week, around the globe picking up small fractions of abandoned, forgotten, or unclaimed rights, thereby creating or amassing a juggernaut of wealth. To a corporation, this is just business.

The other perspective is that a corporation is a team, created to work together to acheive the same objectives. The question then becomes who gets to join the team. And another layer of complexity is who gets to keep the benefits of the team. Traditionally in America, many of those intangible benefits accrued to the community. Now they have been defined and are being harvested by those willing to or able to do so. So everything that can be becomes privatized, corporatized, or governmentized. In other words, access by the least among us is limited.

So, to come back to your question, risk is not pushed back, it just was rejected by those who harvested the things of value. Others have seen risk as something someone is willing to pay to avoid, so they create a market in risk avoidance. As that market becomes "accepted" by society, the uninsured become the have nots.

Now you are talking about something slightly beyond this concept. It is the purposeful jettisoning of risk by someone or a corporation that took it on as part of a business strategy. If a business took on a risk, and survived, do they then have the right to change thier business plan? In business school, you probably learned that if it was good for shareholders, the company should do it. But here is the rub, is it ethical for government officials, who are fiduciarily responsible to "the people," to help private business adjust their business plans?

We have a separation of church and state, meaning state does not regulate religion or belief, and church does not pick and pay for leaders. I one possible utopia, maybe what would work is a separation of business and state. The state is still the enforcer, and it has the fiduciary responsiblity to ensure business can function freely (just as it does for religion), but business does not get to go to government to get a do-over. Laissez faire means the right to live and die by your own actions. And what a good place to practice but on synthetic entities.

Your observation about a start-up is spot-on; far too many VC folks have never actually been in the trenches and had to eke out the month and make a payroll. They are well-trained by the best schools we have, but even the best schools don't actually teach you all the nuts and bolts require to grok business at work, or the real risks involved. Coursework does actually discuss maximizing utility, but cripes, there are people attached to that, bringing with them all the gray stuff of humanity. The translation to cold, hard numbers just doesn't work.

I guess that's one of the key issues that I'v enjoyed in Dave Pollard's work at How to Save the World; he delves right into that gray goo and tries to mediate that number-centric business with humanity. What I think we need, particularly after reading all his work over the last 3+ years, is better human networking. How can we find the resources we bring so disparately to the table amongst ourselves, so that we can maximise our utility while competing against the corporation that never sleeps? More on this as we move forward; I'm working on this.

Sorry, guys, hope you'll figure out the gist of what I was saying. I'm still stewing on this, will have more to say, especially in response to still living's comment.